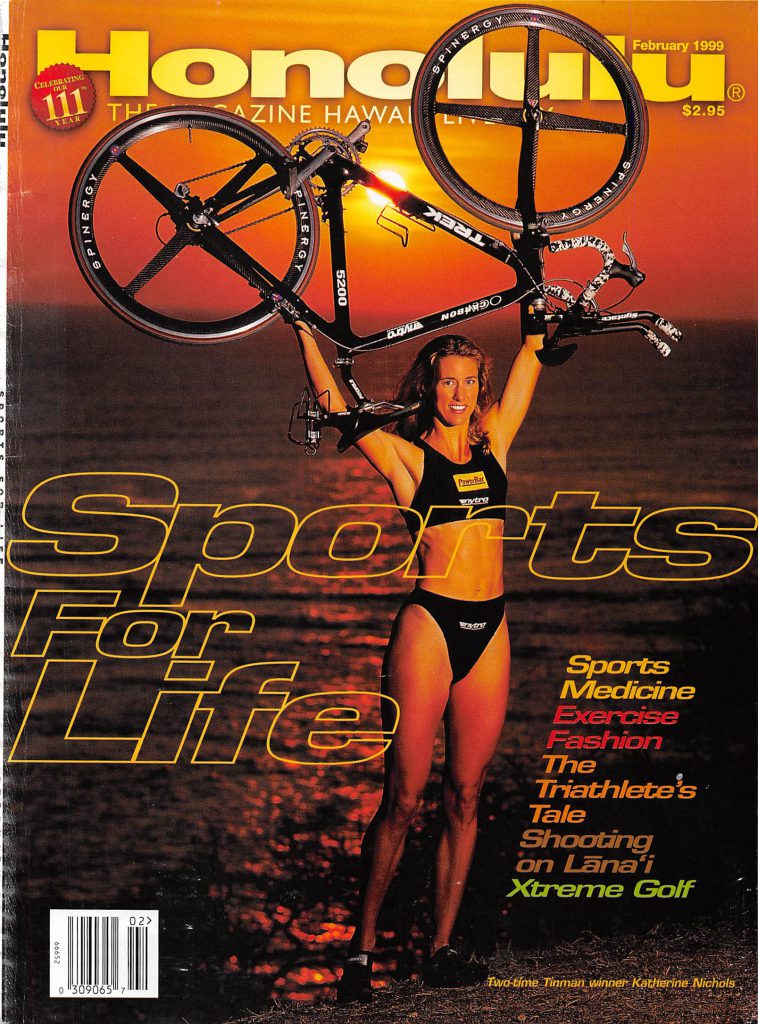

Honolulu Magazine

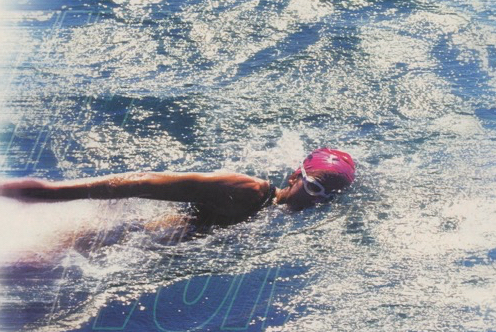

Submerged in water up to my neck, I barely notice the first traces of light piercing the ocean. I’ve been awake for hours. It’s 5:44 a.m., that eerie time between darkness and blinding sun. That silence between the nervous hum of voices and the crack of the starting gun. The moment when you can no longer avoid the two hours of pain ahead.

Deep breaths, I tell myself. Adrenaline pumps through my body, fueled by the 1,100 other people pacing, shivering and treading water around me as they await the start of the 18th annual Tinman Triathlon. Their presence is everything. Without them, it’s just another workout.

I situate myself in the middle of the first wave of swimmers along the imaginary starting line. We greet and survey each other as we jockey for position. An anxious giggle floats over the crowd. All so civilized for a group preparing to kick, scratch and swim over one another without a second thought. Testosterone radiates from everyone—most powerfully from those who expect to win. Women are no exception. Once on the starting line, our competitive fires rage like any man’s. Sisterhood all but disappears until the finish line.

Bang! Fifty hard strokes in this half-mile swim usually help me jump to the front to avoid the crowd, but today I’m not prepared. Having barely made it here, I’m still rattled. The fear of going anaerobic—breathing too hard too early—makes me hold back. The crowd presses in on me. Someone kicks me. (But not in the face, so I consider myself lucky.) I lose myself in a mass of bodies and white water, sensing my direction but seeing nothing. The strong taste of salt wastes through my mouth. Hands grope my back and legs in search of clear water; I’m doing the same to some anonymous, lycra-clad body. It occurs to me that in any other situation, this behavior would be considered barbaric.

At last the crowd thins. A man and a woman quickly position themselves behind me to catch my draft—a legal annoyance that I must not allow to distract me. I count my blessing: My goggles have not been ripped from my head, and I glimpse the destination buoy about 600 meters away. After an inauspicious start, I’m off to my slowest swim ever, still borderline tachycardiac despite my lethargic pace. Make it happen, I tell myself. If you formulate excuses right now, you will lose. Don’t even think of them!

That’s he way you talk to yourself when you are expected to win, but fear you will not. Competing is about rising above the self-doubt that threatens to plague every athlete, convincing yourself that you’ve prepared properly and can meet the challenge—even as you wonder whether your body will respond to the pressures and demands on this particular day.

One way or the other, I am on my way.

I’d had a difficult morning long before the starting gun. At 4 a.m., still at home, I checked my equipment for the 27th time, and decided to top off the high-pressure, glued-tires. The rear valve emitted a suspicious sound, but I thought nothing of it. The tires had held air perfectly all night.

I also fingered the bandage secured with adhesive tape over the infected blister on my toe, sustained after walking too far in high heels for a business lunch. I hoped it would hold though the swim because I planned to bike and run without socks, and an open, raw infection rubbing against my shoes for nearly two hours was one more agony I didn’t need.

Finally, my hand rested on my pocket and gripped the most important race accessory: my asthma inhaler. Just as I thought 6’6 (my father’s height) was the average stature for a man when I was a child, I believed that weekly shots in both arms, a bedroom stripped of everything that might collect dust, and pediatrician house calls in the middle of the night were normal. My mother got so tired of taking me to the doctor’s office that she learned how to administer shots herself; each week I sat on the kitchen counter and felt her inject drugs that were meant to boost my immune system. When I was 7, my parents asked a specialist what they could do to help ease my symptoms; this very progressive doctor said, “Let her try swimming.” Now, thanks to my parents’ encouragement and patience, my asthma is only a problem when I’m ill, in certain weather and when I exercise.

Careful not to awaken my husband and two children, I wheeled my bike into the darkness. The ride to Ala Moana Beach Park was, as always, a way to warm up and search my soul. Darkness is heavy at the hour. It’s not easy to start your day when every fiber in your body screams for sleep. Will you feel good? Can you handle the pain? Will your equipment fail you?

This is the gamble of each race: You never know until you’re in the middle of it. The reason professional athletes do little else in their lives is because they can’t. It’s not about time, really. It’s about energy. It’s about focus. It’s about stress. There is only so much you can handle before you lay it all out on a given day. And as anyone with multiple responsibilities knows, the fuller your life is, the slimmer your chance of putting together the perfect race.

The Ala Wai Canal is my guide. The smell is tolerable, and the palm branches reflected in its surface whisper warnings of a difficult bike ride: a head wind out to Hawaii Kai. I hate fighting the wind. As I pass other competitors on their way to the start, I remind myself that the wind does not single out my bike for torture. Everyone faces the same conditions. Still, I wonder if my hopes for a fast time are unrealistic.

I arrive at 4:30 a.m., basking in my preparation. Two years before, in my first Tinman, I got stuck in a massive line and barely made it to the start, without a warm-up. Lesson learned.

I weave my way through the darkness and rack my bike. Simply out of habit, I check my tires. Soft! (An ominous adjective, except maybe for skin.) In the 23 years since my first triathlon, I’d never felt that sickening give in a tire before a race. Despite my time cushion, my mouth goes dry. My decision-making skills exit. I ask people around me—as if they know or care about anything outside the realm of their own race—what to do.

“Get a floor pump and see if it’ll hold air,” one suggests. A pump! Brilliant! I zigzag through a mass of humanity and equipment, over puddles and under ropes in the poorly lit parking lot now teeming with activity. To no avail. Hand-held pumps are abundant, but will not supply enough pressure for these tires. Then I see it—the technical support van. With a mechanic!

“Do you have a floor pump I could borrow?”

“We did. It just broke.”

Sweat beads at my temples; I run back to poll my disinterested rack mates.

“Better change it,” is the consensus. “It won’t hold air anyway.” Of course! What good is my spare tire if I don’t even start the race? I strip my bike of water bottles and other accessories, then walk to the mechanic, smiling brightly, hoping the smile will encourage his help, knowing his help will save me time and rescue my hands from the agony of stripping a glued tire from its rim.

Glue! Only a trace remains on the spare. Without a proper amount of glue on a new tire, it can easily roll off the rim during a sharp turn. I consider the turns in the race—all of them fairly tight. An image flashes before me: my body—protected by what amounts to little more than a bikini—sliding across the asphalt on Kalaniana’ole Highway.

“Do you have any glue?” My smile freezes.

“Nope.”

I ask his diagnosis on the original tire. After much fiddling and inspection, he declares a valve problem caused the leak. He thinks he could fix it with this or that or maybe some tape. I look at him hopefully.

He shrugs. “But I don’t have anything here.

Other people crowd around. They need help, too. I feel guilty that I’m monopolizing the mechanic. But I justify my selfishness because I have an earlier starting time than most. He begins to change the tire. Because we don’t have an adequate pump, I offer my CO2 cartridge, designed for a single inflation of this tire to the perfect PSI. After all, what use is it without a spare? He attaches it to the valve.

POW!

My hand flies to my chest as though someone has shot me. My spare is gone. Not just soft and limp, but completely dead. I look at the mechanic. “ Guess it was an old tire,” he says. “Sorry.”

I open my mouth to say that the tire had not been ridden, but stop myself. Who cares?

Nobody appears to have a cell phone, so I beg people in the vicinity for a quarter. One spectator digs two from is pocket and dumps them in my hand.

My shirt is soaked with sweat now, despite the warm-up I’m not doing. I run through the parking lot and cross the street to the pay phone. Riiinng. Will my husband ignore the phone? Today, of all days? It’s 25 minutes to the start of the race. Every ring is lost time. Four rings later, I hear a mumble on the line. He’s half-awake, I remind myself. Speak slowly and simply.

“I need you to pump up the tire on my spare wheel and bring it to me and I know you have to put the kids in the car and they’re asleep and I know you have to drive through Waikiki and you can’t actually come into the park so I’ll try to find you out on Ala Moana Boulevard near the shopping center and if I’m going to get back in here and put my bike back together and make it to the start a half-mile away I need you here in 10 minutes. Please can you do it? Please?”

Silence on the other end. I tap my foot and fiddle with my ponytail.

“So—what’s the problem?” he asks.

I try again. And wait.

There isn’t much my husband hasn’t seen. He watched me before every high-pressure cross-country and track race at UCLA. He’s watched me prepare for races a thousand times. He’s even watched me push out two babies. But this is a new one.

“Please, it’s the only way I can make it to the starting line.”

“Of course I’ll help,” he says. “But I don’t know if I can make it.”

“That’s OK. Just try.” It’s my nature to go down fighting. Without a word of complaint, he swings into action. And what have I done for him lately? Bicker about deadlines and illnesses and injuries, leave piles of laundry, uncooked dinners, and a June Cleaver nightmare in the wake of my preoccupation with wearing No. 2 (the number given to the female defending champion). I’ve forbidden everyone in the house from sharing cups or utensils with me lest they pass along some dreaded pre-school, kindergarten, or UH Student Health disease that would prevent me from competing.

Thankful that I have someone in my life who forgives these faults and helps me whether or not I deserve it, I run back to the van—and stumble into chaos. The mechanic is surrounded. Helpless and lost, people turn to me. “Do you have an extra helmet?” “Can you pump up my tires?” “I forgot my number.” Suddenly, I’m part of the crew.

My bike is still in pieces. Twenty minutes to race start. My transition area, which should be perfectly organized, looks like my son’s bedroom after his friends have visited. I haven’t stretched. I know my husband won’t make it. I want to cry.

I pull myself together, run to borrow a cartridge from a generous rack mate, and plead with the mechanic to give the original tire another try. Diplomatically, I volunteer to take care of the participants needing his help. So with a hand-held pump, I start inflating tires and watch the mechanic’s every move.

Failure to resuscitate! Confirming the valve leak diagnosis, he takes over pumping another competitor’s tires to let me wallow in the hopelessness.

Then Faye, owner of The Bike Shop and Tinman race director, approaches with good news (and a cell phone!). “We have a rear wheel in the van that you can borrow.”

Saved! I call my husband, hoping I haven’t missed him, which would require a trip out to Ala Moana Boulevard. He’s breathless from rushing around the house.

“I have a wheel!”

“Wait,” the mechanic warns, still trying to help me despite the throngs groping for his attention. “The gearing doesn’t match.” We count the sprockets. I can’t see clearly in the darkness and must recount three times. Sure enough. If the gearing is wrong, the chain can fly off or jam and cause an accident.

“I guess I need the wheel after all.” I don’t hang up. Sensing my hesitation, my husband waits. Fifteen minutes left.

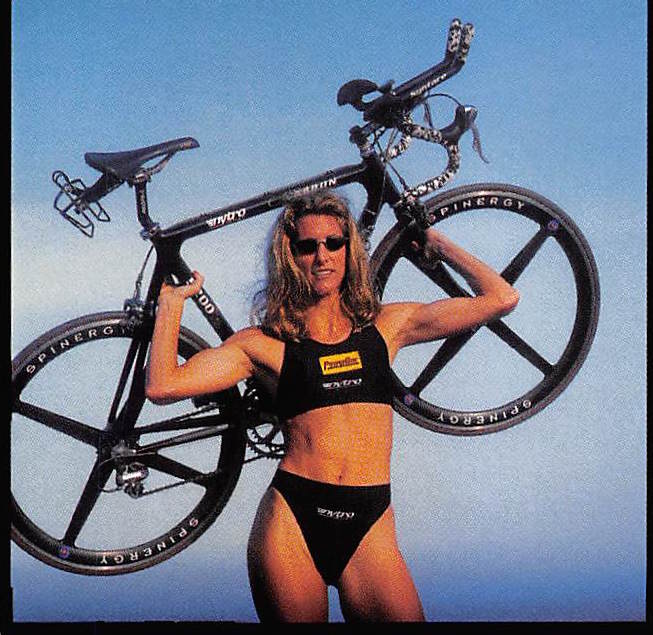

Then I hear a familiar, accented voice behind me. “Are you having a problem?” Raul “Boca” Torres de Sa, “Tri-god” to many women in the Islands, strolls up in all his tanned, muscled, Brazilian glory. “I rode my bike here, and I’m not racing. You can use my rear wheel.”

I gasp. “Does the gearing match?” I am a woman in distress. Suddenly a cowboy rides up, ready to scoop me onto his horse and whisk me away to safety. But secretly, I doubt the whole scene. Surely he’ll gallop by, botch the pickup and leave me in the dirt on my rear end.

“Yes, it matches.”

“Really?”

“Yes.”

I thank my husband and tell him that after all his trouble, I’m going to ride off on another man’s wheel.

Raul puts his arm around me. “Now go and fix your transition area, get warmed up.”

“My stuff’s over there. Do you see?”

He whispers. “Calm down. Do what you need to do. Warm up. Focus. Your bike will be ready when you get out of the water.”

I hug him.

“Just be careful how you start out,” he warns. “Watch the gears. And don’t think you’re at a disadvantage. This is a good rim.”

A good rim? I don’t care if it’s made of lead. The next day, however, he admits with a chuckle, “Feel how heavy this is. It probably cost you at least a minute.”

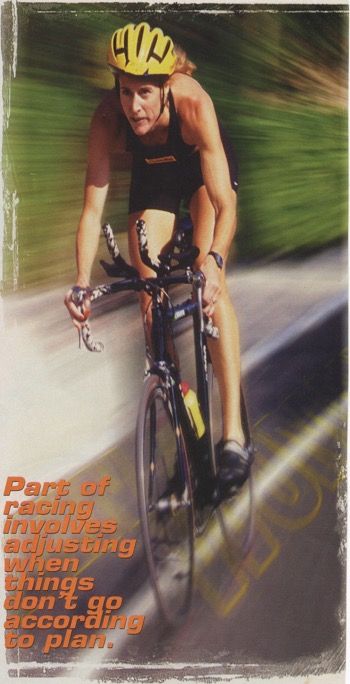

Sure enough, Tri-god had the bike ready. Out on the 40-kilometer ride, I struggle to catch my breath, untie the drawstring on my suit for more breathing room in my new, uncomfortable yet aerodynamic position, and pray every time I shift gears. I exited the water with Big Island sensation Lokelani McMichael, 11 years my junior, sitting atop a bike 11 times as nice. I expect her to go with me, and am pleasantly surprised when I drop her by mile one. Maybe she’s having problems of her own today.

Approaching Diamond Head hill, I round the corner and look for my friend Heather Jorris, pregnant and not competing this year, to report on my position. At worst, I must be second or third. I don’t see Heather. Instead I hear someone shout, “Way to go! Only three women in front of you!”

Three? Who? How far? Information Heather would’ve provided because she understands exactly what I need to know. Just getting to the starting line exhausted me, and now I have to hammer the bike ride to put myself in a safe position for the run. Part of racing involves adjusting when things don’t go according to plan. But I start to wonder if anything will go according to plan today.

Again, I count my blessings. The wheel works. The first female comes into sight at the top of Diamond Head hill. I pump my legs and say, “Nice swim.” Hopefully the combination of a friendly compliment and aggressive pass will dash any hope she has of hanging on to me.

On the highway I scan each rider for a bathing suit top—often the only way to distinguish females in a race. A few men crank by. The next woman comes into sight at Kalani High School. The third and last at ‘Aina Haina.

A sense of relief floods me. I ease off on the pain pulsing through my back and quadriceps. It doesn’t matter if the girls stay right on me the entire bike ride. The run is my strength; I am exactly where I need to be.

“Way to go!” people shout to me along the return ride from Hawaii Kai. Focus is essential to win and to avoid an accident, so I never respond to cheers. Yet I feel a pang of guilt as I ride, and hope the spectators don’t think me rude for staring straight ahead. I concentrate on my form, making perfect circles with my legs, contemplating the run ahead. Pull up. Push down. Relax shoulders and face. Exhale slowly. But I never let the pain get too intense. At least not the way I would if three women were still in front of me.

With help from volunteers in the transition area, I rack my bike and double-check my position. You never want to lose a race because you didn’t have all the information. “Are any women ahead of me?”

“No, you’re it.” Other volunteers find my bag and lay out my shoes, an advantage many other participants do not enjoy. I appreciate this and thank them.

I begin the 10-kilometer run with confidence, remembering what I found in myself last year when two women were ahead of me until mile four or five. Despite feeling undertrained because of a long illness—the result of a writing assignment on the Amazon River that May—I was able to edge out Heather. She’s an athlete I deeply respect, and I know there is not a woman in this race today as tough as she is. So unless disaster strikes, I can do my job and greet my children at the finish with a smile. The only disappointment: I’d hoped my time would be closer to the women’s record, 1:50. But after the slow bike split, I know I can’t run fast enough to get near my goal. I try to let go.

The awkward, detached sensation every athlete struggles with when he leaves behind his bike and begins running is the real test of a three-sport race. Each runner is sure he feels worse than everyone else on the road, sure that nobody suffers as he does. But the truth is that a common misery bonds you.

So I bond with the men breathing around me, pull myself into their pace, use their energy. I inspire them, too; few men will allow a woman to beat them if they can possibly help it.

Cresting Monsarrat hill, we breathe a collective sigh. The worst is over in this two-hour ordeal. The glaring sun makes me suddenly aware of the heat. My sunglasses save me. Every aid station is welcome sight; each sip of liquid cuts the dryness of my dehydration.

Some racers are still finishing the bike ride; their cheers lift my spirits. How different from the year before, when “Go Heather!” rang from every direction (including the media truck!). As Heather and I ran side by side last year, I felt like the unpopular kid in school, the last one chosen for the kickball team. So I surged every time I heard the calls. Today, however, I’m the only one to hear my name. I feel fortunate that other competitors find me worthy of a lost breath in the middle of their race.

I soar down Diamond Head hill. My legs have found rhythm now; my stride is long and smooth. Only the endless stretch along Kapiolani Park remains. It seems to last forever, but makes the sight of the finish banner that much sweeter. Last year I paused and waited for Heather to cross the finish line with me, something I’d never done in 25 years of racing. With the pressures she had faced that year, it just seemed like the right thing to do. Despite her excellent race and personal record, she and others would see her performance as a “failure” because she was expected to win. I understood this and wanted to spare her that disappointment. I reached for her hand, but she would not take it. She wanted me to have the victory all to myself.

No such drama this year. Just a few television news camera recording the moment, a few sportscasters asking me for comments when I can’t separate my tongue from the roof of my mouth and I’m fighting a mild urge to vomit. When I watch the news later that night, it occurs to me that’ve never been on television when I’ve actually showered beforehand. Dry hair and a touch of lipstick are distant fantasies.

Heather and I teach a triathlon clinic for the Honolulu Club, and I wait at the finish chute for our participants—most of them first-timers—to cross the line. Their sense of accomplishment gives me greater satisfaction than my own victory.

“Did you win?” my children ask me in the park, as they often do after races. For a moment I get philosophical, take the opportunity to teach that winning is far less important than personal improvement and participation, no matter what level. My discourse last about 8 seconds—until they catch a glimpse of the Tinman, a man dressed as the character from the Wizard of Oz, a race mascot who’s at the finish line every year. Screeching with delight, they scatter my words of wisdom and run off to greet him.

The year before, Heather and I were featured on the front page of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin sports section. At the edge of the photo lingered the Tinman.

I’ll never forget the way my son ran into the house, waving the newspaper and shouting, “Mommy, mommy, look! It’s the TINMAN!”

Even with a house full of writing deadlines and laundry, it’s easy to get caught up in the event. But there’s little danger of losing your perspective for long when you have children to remind you of what’s really important.