Since 14-year-old Jeremiah began horseback riding in Waimanalo, his mother, Laurie Kahiapo, has noticed that he behaves better, engages more appropriately with other people, and has improved his physical coordination. This kind of progress means a lot for Jeremiah, one of nearly 20 autistic or otherwise disabled children who participate each week in Manawale’a Riding Center’s Therapeutic Horsemanship of Hawai’i program. “It’s really good for him,” says Kahiapo of her son. “He’s so much more confident.”

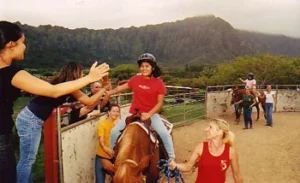

Left to right: Volunteers Kristyl Kim, Prakay Thommas, Marie Grigg, Dr. Chris Melhan, Dana Ishii, student rider Kaily Ching and volunteer Misty Lawrence, shown at the Manawale’a Riding Center in Waimanalo. photo: Val Loh

Horse therapy is designed to reach children with physical or verbal disabilities that inhibit socially appropriate behavior or participation in activities or sports most children enjoy. Some have trouble walking, and struggle with balance and lack of muscle control. For many, speaking is laborious or impossible.

Riding sessions begin with equilibrium and coordination exercises on a saddle affixed to a wooden pole known as “Mr. Woody.” Daniel, a 10-year-old with Down syndrome, reverses direction in the saddle, which also helps strengthen his back muscles. Daniel is more advanced than many of the students. He starts his day shoveling out stalls and putting away tack before he gets to ride. If he follows directions, he gets to trot the horse.

“It’s really sensitive,” says Daniel’s mom, Jan Takushi, who asked the team to help improve Daniel’s work ethic, and hopes that one day he can work cleaning stables and grooming horses. “It’s not one size fits all. It’s just whatever your child needs. They go out of their way to give your child confidence.”

Maggie Young, an occupational therapist who volunteers with the children, agrees. She became hooked on the program when she witnessed a dramatic improvement in a young girl with cerebral palsy. Tight adductors caused her legs to cross, inhibiting her gait. After she rode, those muscles stretched out, and when she walked from the ring to the horse’s stall to feed him a carrot, her pace and balance were greatly improved.

Youngsters sit or lie on the horse’s back–with a minimum of three volunteers guiding the animal and spotting the child–and are able to feel what’s called the “three-gait movement,” which a clinical setting can’t replicate, according to Patti Silva, a North American Riding for the Handicapped certified instructor at Manawale’a. “They gain the benefit of the horse’s motion, as well as the warmth. It’s amazing how much they will immediately relax. It’s so heartwarming, especially when you see the smiles on their faces. A lot is painful for a child who can’t walk. Watching these children improve is so rewarding.”

This prize may come in the form of the smallest signals. Micah, a 7-year-old autistic boy, sees little and can’t speak at all, walks and holds himself up with difficulty, and rebels against much of what he is asked to do. Yet when he arrived at the ranch, Moloka’i (a gentle giant quarter horse) nudged and greeted him with a wet nose and a friendly snort. It took a long time to prepare Micah to ride. When he was ready, Silva and the volunteers held and supported his lurching body and walked around the ring for half an hour, calmly encouraging him. After singing “Itsy Bitsy Spider,” they turned on the overhead sprinklers, showering everyone with drops of water. Finally, a smile brightened Micah’s face–compensation his helpers welcomed enthusiastically. After the ride, Silva walked him over to the feed shack, where she guided his hands through a barrel and asked him to grasp one pellet at a time–a difficult task that he completed successfully, earning him lots of praise.

“We’ve never seen children work so hard to accomplish something that the brain would not carry through,” she says.

Kahiapo believes the combination of loving volunteers and an exciting activity they all want to try motivates children unable or unwilling to engage elsewhere. “He does what they ask him to do,” she says of Jeremiah–behavior Kahiapo doesn’t always witness at home.

Rosemarie Grigg, a therapist and autism consultant who brings her students to Manawale’a, says that some of the horses get to know the children and challenge them to work harder. It seems that Moloka’i, for instance, understands that Jeremiah is capable of speaking clearly. So when Jeremiah mumbles, Moloka’i stubbornly refuses to move unless he says, “Walk on, please,” in a comprehensible voice.

Anyone is invited to visit this Hawaiian oasis nestled at the base of the Ko’olau Mountain Range.”Horseback riding has always been something for the more affluent families,” says Silva. “We don’t ever want any family to not come due to a financial situation. What matters is that they come and benefit and enjoy it.” This is why the nonprofit organization charges only $5 per session, relies heavily on some 70 volunteers, and covers expenses with grants and donations.

After dismounting, students thank, praise, and kiss or pat the horse. Then they retreat to a shady lanai for snacks of apples and watermelon with the dozen or so dogs wandering the ranch.

“I would love to give you clear outcome measures,” Grigg says of the benefits. “A lot of this is subjective. But I definitely see increased attention, eye contact, coordination and social skills.”

Then again, a dazzling smile on a child’s face may be all the analysis anyone needs.