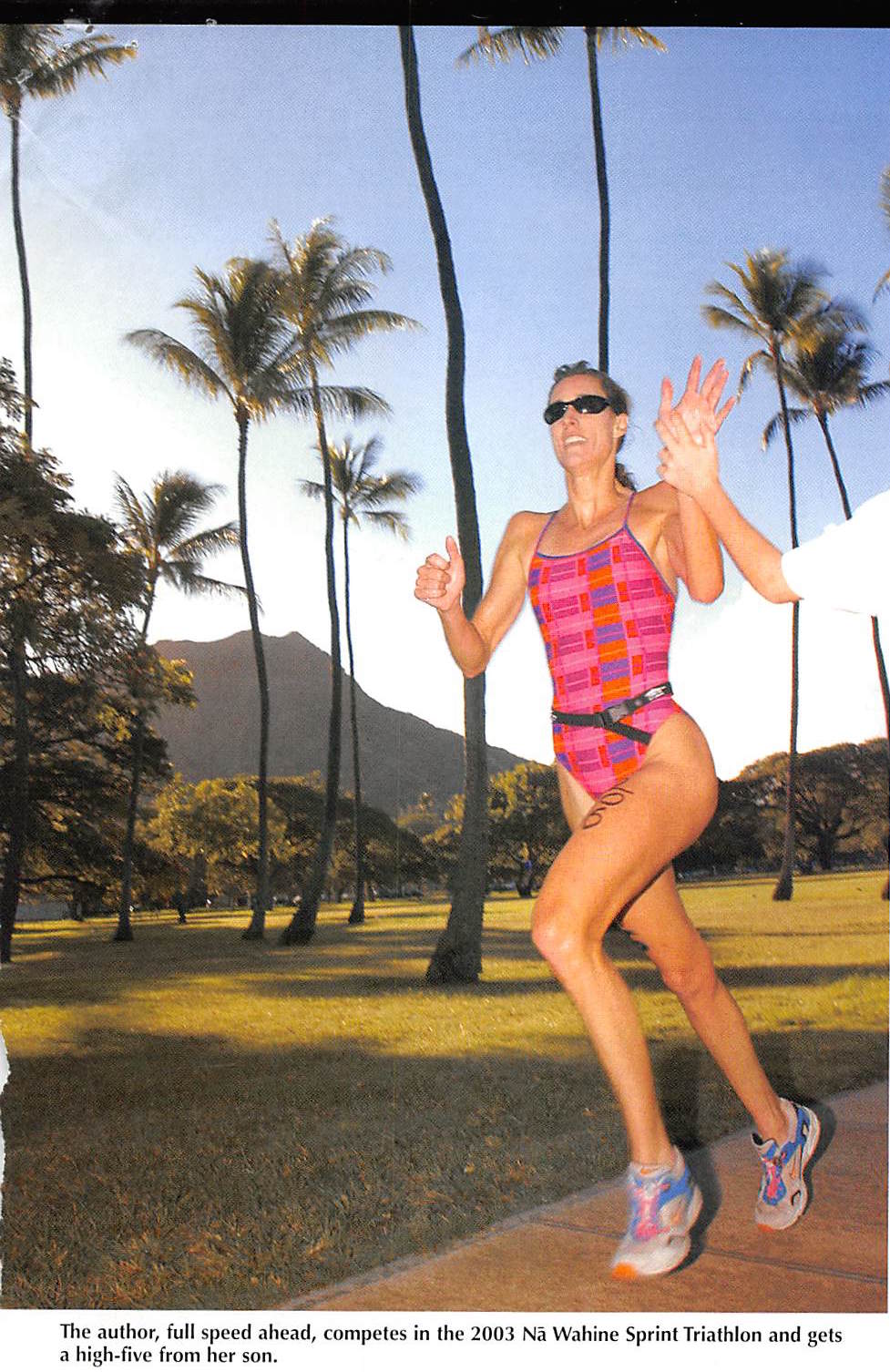

Aloha Airlines Magazine

My once strong arms are no better than two strands of pasta. I’m pulling salt water the way I have since I began swimming competitively more than three decades ago, yet viewing the same rock. I float briefly to rest my noodle limbs, clear my goggles and scan the horizon for a buoy. It’s the first leg of a triathlon I have a chance to win. Correction: had a chance to win. A pre-race buzz still radiates through my body. Not the lazy, semierotic tingle after a glass of wine or the exaggerated heart thump before speaking in public. It’s a vibrant feeling, punctuated with hyperawareness. And that consciousness tells me that my performance today won’t be pretty.

If this is optional, why am I out here suffering?

Particularly astute observers point out that I am getting older. No longer favored to win. Don’t even get asked to speak at the pre-race seminars anymore. Could be lingering over a cup of Starbucks and the newspaper. Or even relishing the last few moments of a pleasant dream.

Yet, confronting pain and not turning away but stepping further into agony so deep it stiffens your fingers and numbs your face—and still not winning—teaches me everything I need to know about myself. It redefines success. Changes my perspective. Gives me courage because it erases my fear of failure. Every approach to the starting line represents a new chance.

Danger Within

Unfortunately, many of those opportunities over the years slipped away in mistakes, poor preparation, illness, faltering focus, the needs of others that had to come before my own desires, circumstances I couldn’t control and couldn’t overcome. I fell short of my potential, frustrated teammates. I failed when I needed to perform brilliantly, and achieved brilliance when it didn’t matter. But I showed up at the next race. And the next. And soon I learned that often I did conquer, and did not disappoint. But always there was the risk.

Indeed, an athlete in his 20s told me it is the danger of that failure that drives him to compete. He thinks that pushing beyond what you believe is possible is the only way to know yourself. “Once you have done this, the knowledge you attain transcends the sport,” says Brian Cadman, a former Harvard swimmer. After racing hard, teaching 60 college students or defending his doctoral thesis “seems quite easy.” Other athletes agree. Competition, they tell me, is not really about coming across the finish line first. Rather, it is a cerebral crusade within oneself, an emotional test of personal limits, manifested in what appears to be a purely physical arena. The perseverance that rises from that battleground is the real reward.

Hot winds gallop across the lava fields, bent on hurling me from my bike. I feel so alone. Probably because I am. My competitors have zoomed ahead, leaving me to struggle with each pedal stroke, my lungs catching on the remnants of a flu that kept me bedridden the previous week. Miles remain. I am facing the inevitable moment of crisis. I remind myself that calamity isn’t defined by tribulations, but rather by how you approach them. Isn’t anything meaningful littered with hurdles? My mind drifts to impediments in our daily lives. Last time I looked, staying married, raising children, keeping a job and caring for family members required a bit of effort. But is today’s event worthwhile? Does it matter now that I am a long way from both the start and the finish? Squinting, hunching, whimpering against the elements, I convince myself that a path around or through today’s barriers will appear if I look hard enough. Better yet: I can stop thinking so much, put my head down and go.

Do As I Say …

By encouraging me to try again and again, competing also guides my parenting (talk about going to the starting line repeatedly!). And not just in the raw, challenging moments, but during the easy ones, too. Children often participate in sports for the social benefits. There is wisdom in this, and I try to remember that their objectives may differ from mine, and to respect them as individuals in pursuit of their own dreams or the ideal post-game snack. My athletic experiences also keep me relatively quiet. Painful race moments come to mind when I listen to well-meaning parents holler at their children from the sidelines of soccer and baseball fields, triathlon courses and swimming pools. “Pedal faster!” “Get the ball!” “Run!” “Shoot now, now, now!” Having heard it all as a contestant, I feel that I know the difference between encouragement and impossible instructions. So I clap and smile and hope that my example, rather than my yelling, will inspire.

The Harvard swimmer who grew up with that model says racing teaches him just as much during the training phase. “There is a long road before actual competition,” he says. “Discipline, desire, knowledge and creativity are all critical elements of a training regimen. Discipline to stick to a training plan—for it is the days that you don’t want to train that improve your performance. Desire to have a goal in mind that you are willing to sacrifice for, knowledge of how to achieve a goal and creativity to adjust the plan in the face of adversity.” Whether it’s a triathlon or a doctorate, the preparation is long and accomplished only one day at a time.

Similarly, my history in racing also assures me that I can work toward an elusive goal. The genuine possibility of failure does not immobilize me. So I dive into projects outside my area of expertise on a regular basis, because I know I can learn from others, recover from bad days, adjust my plan, dig deep when it counts, accept that I might not succeed on the first attempt, or ever (recalling my history on a tennis court). This, above all, I hope my children will discover for themselves.

Primal Urge

Productive lessons are motivating, to be sure, but there’s an even deeper attraction to racing. A physical test so inherently mental—without pretense of higher-level thinking—carries primal undertones. The experience feels like a throwback to an ancient existence in the woods, where survival of the fittest prevailed. Instinct, brute strength and mental focus kept one alive. Competing makes me feel as though I am one of those survivors. Would I have perished without a man to hunt for me? Somehow I doubt it. The modern implications are obvious. Knowing how many men I can outrace quietly strengthens me in every social or business encounter, levels the field a bit and softens the atmosphere as it washes away the exfoliating air of intimidation

Triathlete Debbie Hornsby started racing as a way to help her control her weight. But psychological and emotional rewards eclipsed the corporal benefits soon enough. “By competing in and finishing my first Ironman (2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bike ride, 26.2-mile run), I felt more capable than I ever had in my life. If I could do that race, I could do anything, overcome any challenge and succeed in whatever I set my mind to,” says the four-time Tinman Triathlon winner and top-15 finisher in the Ironman Triathlon World Championships. “Competition helped me see a better side of myself and went far in erasing some of the typical female insecurities I suffered. Through training and racing, I learned that I could stand on my own, that I was a survivor and that I was much more able than I thought.”

Go Home Cook Rice

That confidence did not come easily to our sex. Forty percent of the athletes at this year’s Olympic Games in Athens were women. The most ever! chirped the announcers, upbeat about the improvement in 100 short years. My mother and stepmother, both excellent swimmers and University of California-Berkeley and Wellesley graduates, respectively, could not compete in college; there were no sports for women. Title IX—to prevent gender exclusion from activities receiving federal financial assistance (and still saddled with problems)—didn’t take effect until the mid-1970s. The ancient sport of marathon running tried and failed to gain ground when Katherine Switzer registered with the first initial “K” to run the Boston Marathon in 1967, only to be accosted four miles into the race by a race official, who tried to pull off her number. (Her boyfriend, a hammer thrower, protected her through the finish. She went on to complete 30 more marathons, and the Boston Marathon changed its rules to allow women to participate in 1972.) Olympic swimming events still do not include the 1,500 meters for women, and the women’s Olympic marathon debuted only recently, in 1984.

Anyone remember watching a women’s water polo match 20 years ago? How about weightlifting? Or wrestling? Progress was duly noted with the inclusion of those sports for women in recent Olympics. Yet that advancement is far from universal. Several countries sent to Athens women who subsequently faced the wrath of their male countrymen—some of whom declared on national television that women should be killed for exposing themselves in athletic attire. In this country, where showing a little skin can earn more attention than achievements in sport, the best-selling issues of Sports Illustrated feature that other swimming-related sport: squeezing into a bikini the size of a cotton ball. One woman participating in a local race seems so inconsequential, but it can build, move and shift attitudes significantly enough to effect social change. Or at least raise awareness. “The story of women in sports is a personal story, because nothing is more personal than a woman’s bone, sinew, sweat and desire. It’s also a political story, because nothing is more powerful than a woman’s struggle to run free,” notes Lissa Smith, author of Nike Is a Goddess: The History of Women in Sports.

In some regards, not racing when it took so long for women to come this far feels a little like not voting. Many people before us fought for the advantages we enjoy today. What freedom! I can bake cakes and host birthday parties, nurture my family and build a career and prepare dinners, wash dirty dishes and wipe dust from the corners of the living room floor, and later don high heels and a tight dress. Why march for a feminist cause or lobby for a better translation of The Second Sex? I don’t feel the need, because when the mood strikes me, I can go out and race like a man. And somehow that makes everything I do feel like a powerful choice.

Hills and uneven terrain disrupt my cadence during the run portion, humbling me repeatedly. But five miles into the last part of this journey in the thick summer heat, as I watch my goals slide away with my sweat, I salvage some dignity. There is honor in finishing what you start, I remind myself—no matter what happens along the way—even when the only prize is a hard lesson. Today I faced pain and failure and redefined them. I did the best I could. And that tells me everything I need to know about myself.